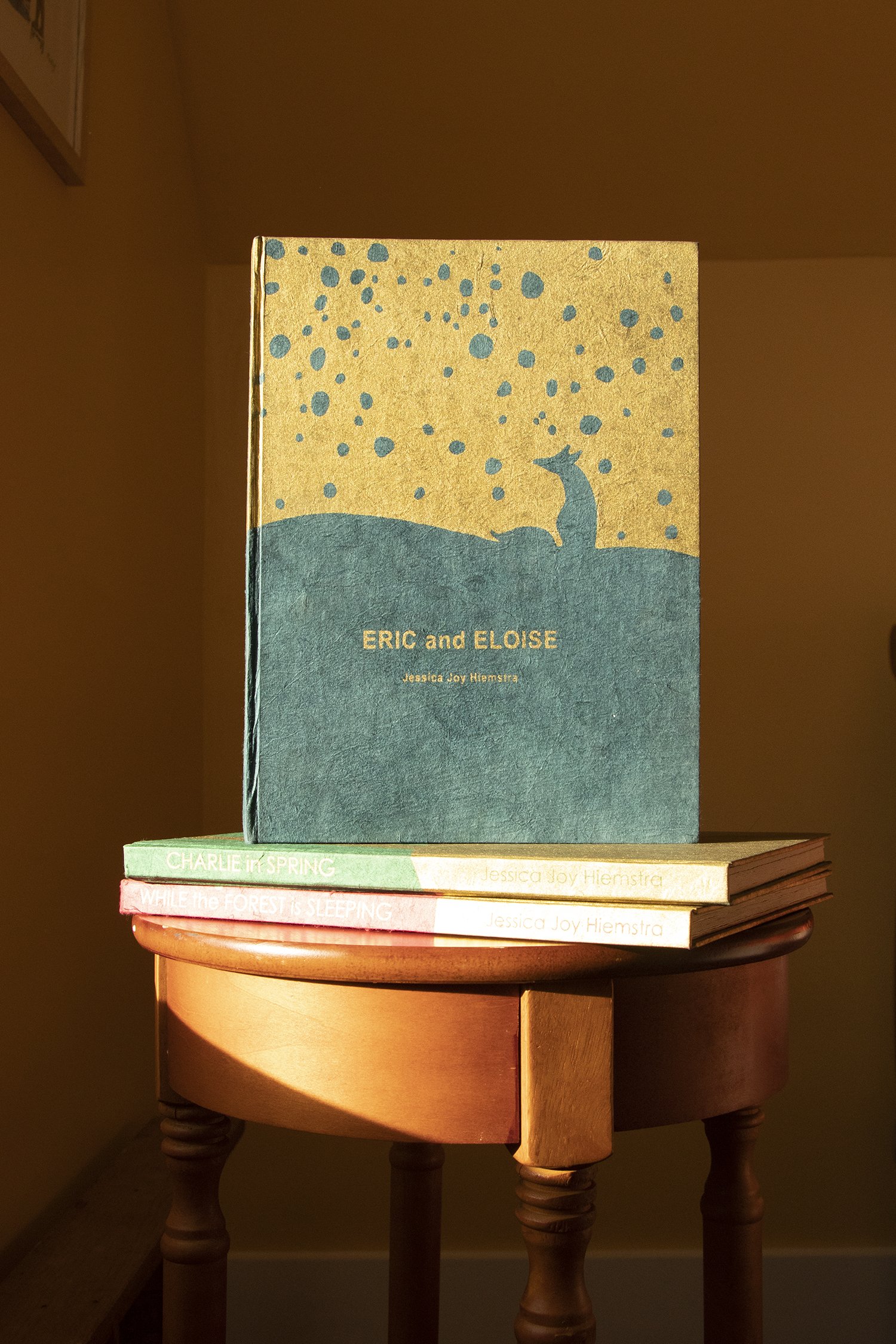

The Holy Nothing

The Holy Nothing

Written and Illustrated by JESSICA HIEMSTRA

Edited by STAN DRAGLAND

Published by PEDLAR PRESS, 2016

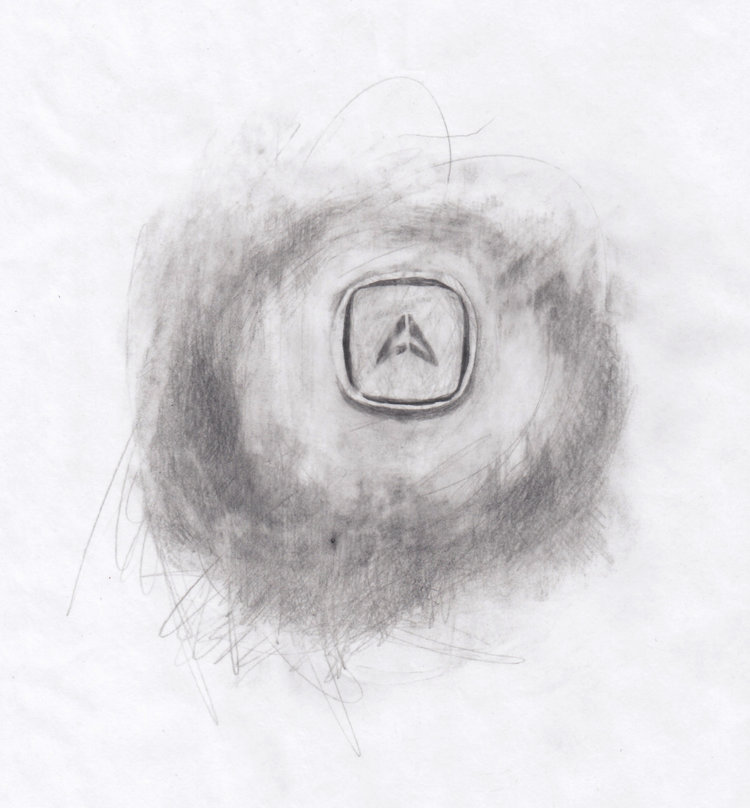

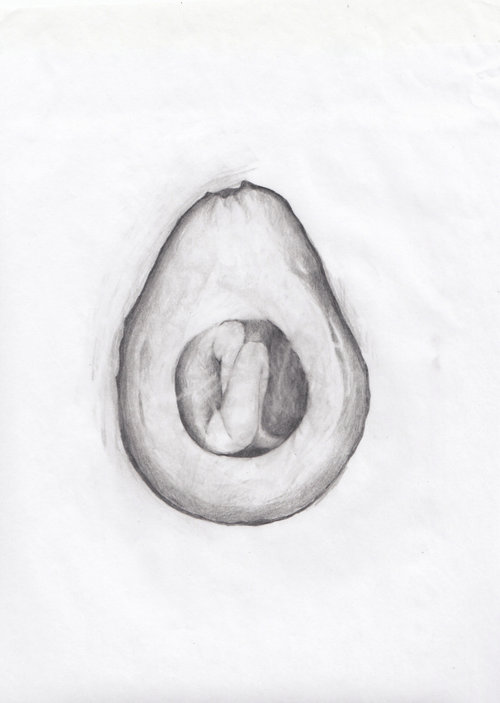

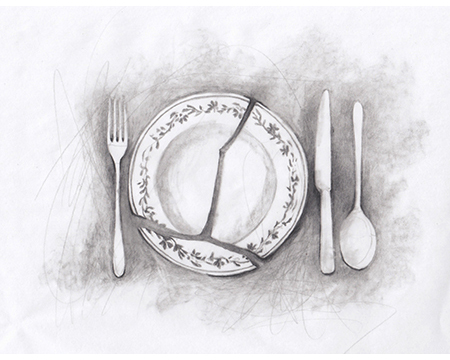

Most of Jessica Hiemstra's newest poems were written over several winters. These were hard poems to write. They arrived both suddenly and slowly. To Hiemstra the poems of The Holy Nothing feel like the slake of a hard moment. Haiku poet, Claudia Radmore, says that Hiemstra's poems want to be haibuns. There's something so painfully unadorned and simple about them. Think of these poems as meditations. Includes 17 beautiful black and white pencil illustrations by the poet.

"Hiemstra’s vulnerability and her resilience are palpable throughout this volume, and she addresses hard personal and universal truths with a relentlessly straightforward honesty. It is this honesty that makes her collection so compelling." - Canadian Literature

“Jessica Hiemstra's The Holy Nothing reads smart like Sue Goyette, tender like Wendell Berry and smartdark like Saint Susan of Musgrave.” - Today’s book of poetry

History

For Yima (1983 – 2013)

While our marriage ended

I miscarried, not justice

or language, though there was that too.

There’s a moment when dead is absolute

but when does dying start?

There are many ways to know we’re

pregnant. I wanted green mangoes

and Yima winked at me. She sat with me

before the swelling Atlantic

with her blue Coleman cooler, her hair flat

where it had rested. She gave me

cold ginger water in a small clear plastic bag.

She peeled mangoes for me.

We will fail to save the albatross

for lack of empathy. I mean our world,

this one filled with barges

and poetics instead of mangoes

and ginger. By albatross

I also mean albatross.

There was you. There was

green mango, slave holes

up the beach in York.

There was Yima and

all kinds of love dying in me.

I carry two countries, this Lion

Mountain, the Rideau out the window now.

I have no home but water.

We all carry two countries: where

we’re born, where we die, here

and hereafter. Three, if we include

the place before we exist, that darkness

God breathes on.

I try to write about Sierra Leone

but end up saying nothing

because I’m sad and sorry and angry.

It’s where I learned to walk, eat yabibi, pineapple.

It’s where I returned to leave our marriage

while reading The Great Fires in a red Adirondack

in a place too honest for us. I think of Yima

biting off the edge of a plastic bag for me,

so I could suck ginger out of it.

The wind caught the bag

whisked it to sea. With bottle-caps

and other shining detritus, it ended up

in the belly of an albatross chick.

That’s all there is, all there was,

all there’ll ever be. Love and trash,

pity and longing. Failure

is because we aspire. That’s good.

There are many ways to set the scales,

words. We may weigh with hunger,

green mangoes, the belly of a starving albatross.

We can flog ourselves with history,

extend mercy to each other. Opa tells me

about his first job in Devon. A Chinese man

sat beside him sexing chicks, handing him females.

Opa packed small hens, tossed the bag of males

in the trash on his way home.

We did it like that then, he says.

I don’t know that we’ve changed.

Yima tells me about holes

in York, the Banana Islands,

people stacked on each other,

too sick to be shipped to England

or Louisiana. The albatross

saw it all and did nothing.

I’m still doing nothing

but eating and reading and wishing.

I watched waves, sucked ginger

through holes in plastic. We can choose

what to do with history and each other.

By each other and history I mean

me and you and slaves and sea birds

dying from what we throw away. Yima

comforted me not with language or justice

but both: when we’re in the womb

we don’t want to come out, when we come out

we don’t want to die, when we die

we don’t want to come back. So it is

with love, she said in Krio.

Our marriage doesn’t matter,

but failure to love

is the end of the world.

I want to feel it all, to come back

even if it kills me, raise the dead.

Plead on my knees.

Yima is washed and carried

to her grave in a white sheet.

The village wears white,

ashobi. Sorrow isn’t diminished

by its frequency. Yima won’t come back.

I want to change history, resurrect her

and Jesus, turn the boats back,

forgive you, forgive us.

Reprinted with the kind permission of Pedlar Press